D&D Against Time

In a few weeks, Hasbro will release the 4th Edition of Dungeons & Dragons, the tabletop roleplaying game that started it all 34 years ago. Because geeks now rule the world, and D&D is the nec plus ultra of geekdom, it pays to give the old game its due. One of the big controversies in the development of new D&D is the extent to which videogames, like World of Warcraft, have influenced its design. The important question about tabletop RPGs and MMOGs is not about influence, but essential difference. What distinguishes the two great acronyms of gaming? Two words: Ancient Greece.

Plato and Aristotle could never have plumbed the depths of WoW for obvious reasons: no electricity, much less computers. The reason the two great philosophers of antiquity couldn’t have played a game like D&D is less clear.

Pong, released in 1972, relied on cutting-edge electronics. Dungeons & Dragons, which appeared two years later, employed technologies that had existed for thousands of years. The odd-shaped dice used to play original D&D – the pyramids, the icosahedrons, the strange gear of so many roleplaying games – are the five Platonic solids. The Greeks had advanced math, writing, drama, myth and lots of leisure time – not to mention an academy at Athens loaded with nerds. So why didn’t Plato ever think to deck out a dungeon for his fellows to loot?

From ancient Babylon to post-WWII Europe, nobody thought of such a thing as roleplaying games, though the materials existed for making them. No one conceived of Dungeons & Dragons until the American Midwest in the early ’70s. Why is that? Why would it take a guy from Minnesota and a guy from Wisconsin to invent D&D just before the Age of Disco? What makes D&D so modern?

This question has many answers, but for now let’s look at just a couple: the two craziest things about Dungeons & Dragons.

Wager Your Darlings

Dungeons & Dragons asks players to make up characters and then gamble with them. Suppose I create a character called Black Leaf. She’s a cute but histrionic thief with shaggy hair who wears sleeveless tunics to look tough. When I put her into play, she becomes my stake in the game. If I make bad choices or have bad luck with the dice, she could die. Even apart from the dice, as the game progresses, she’ll change in unpredictable ways. I don’t really have control over the character I invented.

Yet D&D rewards a well-developed character. It’s a game of economics. Players invest in their creations, then risk them in further adventures in order to improve them again. These improvements could be aesthetic or mechanical, a development in personality or power – or both. If Black Leaf finds a magic rope in a treasure hoard, she can use it to get more treasure or to express herself through rope-tricks. Either way, I’m accumulating an ever-more-valuable, imaginary stake in an actual gamble. Why does D&D work this way?

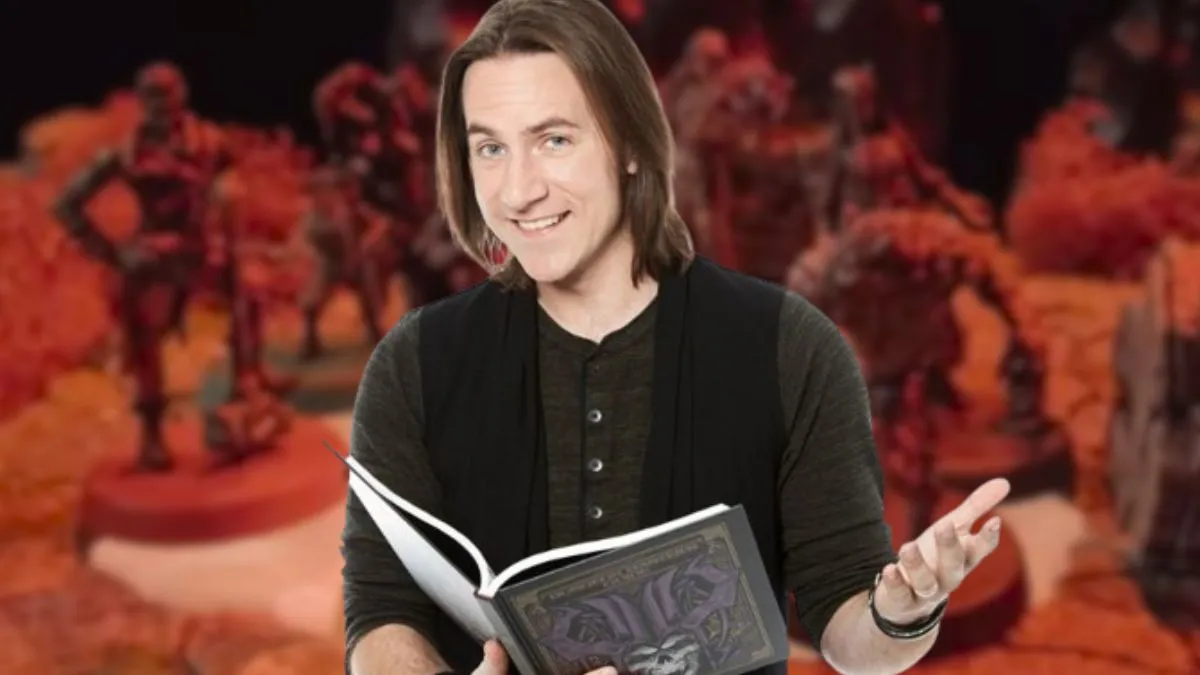

Because it evolved from tabletop wargames. When wargamers assault each other with massive armies of miniatures, they use dice to represent the element of chance in warfare. In the late ’60s, a number of wargame designers – Mike Korn in Iowa, Dave Wesley and Dave Arneson in Minnesota, Gary Gygax in Wisconsin – pushed wargaming toward roleplaying. Wargames downscaled. Miniatures came to represent individual characters, rather than a collection of troops. When Arneson and Gygax published Dungeons & Dragons, it inherited wargaming dice. Fortunately, dice can also model inconsistency and differences in skill level in individual behavior. The randomness of D&D expresses a modern understanding of how people function.

Dice do not, however, do a good job of modeling fiction, and that was another crucial change in the shift from wargames to roleplaying. Where wargames typically recreated historical battles, Dungeons & Dragons took its inspiration from heroic fantasy. The focus shifted from Napoleon to Tolkien. Where history plays out in accord with statistical models, fiction does not. D&D has a sword-and-sorcery heart, but the guts of insurance underwriting.

Gambling with the fires of your own creativity is the first great craziness of Dungeons & Dragons. The second comes from sharing your fire.

Fun is Other People

Consider this scenario: The players need to find the headquarters of the local thieves’ guild, where Black Leaf is imprisoned. The party of characters heads to a sketchy-looking tavern down by the docks to canvas the local criminals. Inside, the group breaks up to make individual enquiries – except for one guy. You know the kind of player I’m talking about. He spots a huge barbarian glowering in the corner and announces, “I’m going to pee on his leg.”

Group dynamics produce unforeseen complications, which often maximize fun. A tough bar fight probably beats rescuing poor Black Leaf. Players can mitigate the chaos inherent in a game’s dice by agreeing to ignore rolls, but they can also intensify chaos by pissing off (or on!) huge barbarians. The group decides whether encouraging mischief-makers adds to the game.

The open, consensual nature of roleplaying games can be habit forming. The strangest and most wonderful aspect of RPGs is that their gameplay influences the business of making them. The RPG industry consists of consumers who are also producers. Everybody who makes games for a living also plays them, and players differ only in their level of productivity. Many players produce characters known only to their gaming group; others publish entire games. The whole community is creative, and this mass of creativity causes conflicts similar to those found in individual groups.

Michelle Nephew and Robin Laws, both game designers, have thought deeply and written extensively about the origins of the collaborative nature of RPGs. Between the two of them, we get a good account of why D&D appeared where and when it did, though neither Nephew nor Laws quite agrees that RPGs are uniquely modern.

Laws emphasizes the importance of where all those early wargame innovators come from: Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin. For Laws, a game of cooperative effort, like Dungeons & Dragons, “had to be an expression of the Midwest.” The consensus gameplay of RPGs reflects the “friendliness and laid-back sense of togetherness” of the place where they were invented, a place with a communitarian history. Surviving together in a dungeon parallels surviving together on the American frontier. This geographical influence has continued to the present, so that with the development of 4th Edition D&D, we’re seeing, says Laws, “a battle between corporate interests and the traditional interests of the gaming community.” The conflict Laws is talking about arises from the fact that, in the RPG industry, gameplay serves as a business model.

Roll for Licensing

Wizards of the Coast, the Hasbro subsidiary that makes Dungeons & Dragons, has taken great pains to develop its Game System License, a legal framework allowing third-party publishers to produce material compatible with D&D. With this document, Hasbro carefully dispenses access to the intellectual property of Dungeons & Dragons. Such a maneuver would be insane in any other industry, but it makes sense for roleplaying games, because they inculcate habits of collaboration and appropriation in players. Hasbro must make its money, but players have to feel that D&D is still a product of their community.

At the other end of the business scale, independent game designers come to informal arrangements with their community. They frequently release their work under the creative commons license, which can allow borrowing of proprietary material. Some online communities of designers, such as The Forge, appeal to “mutualism” in game development, which can mean an exchange of ideas, criticism or even labor: I do artwork for your game; you show me how to put mine on a PDF. Many indie games are very close to being products of an anarchist collective.

Whether corporate or collective, the RPG enterprise comes back to just the sort of group dynamic that you find in an individual game of D&D. The conflict over how open and consensual to make things is part of the creative process.

Thieves’ Guild?

In her work on the origins of roleplaying games (which includes a dissertation on them), Nephew pays attention to how RPGs borrow characters, scenarios, creatures and settings from other media, in both private and published games (appropriating the character of Black Leaf from Jack Chick’s infamous comic, Dark Dungeons, is a much-abused cliché). Nephew finds a precedent for this culture of creative exchange in the pulp magazines of the ’20s and ’30s. In those publications, writers and fans communicated so frequently and with such intensity that much of the writing of that time can be understood as a sort of mass collaboration. Writers also borrowed extensively from each other, yoinking characters or creatures or even the authors themselves. H.P. Lovecraft and Robert Bloch each famously knocked off a character based on the other in complementary tales.

The extensive collaborations of pulp fiction resulted in what Nephew calls a “synthetic mythology,” a shared, imaginary world very much like the ones developed by a group of roleplayers. When RPGs first appeared, synthesizing a background for games quickly became a legal consideration.

The first printing of Dungeons & Dragons borrowed Tolkien’s hobbits and ents. Among the early D&D books that collectors prize most are those featuring copyrighted material used without permission. In its early days, Tactical Studies Rules, the first publisher of D&D, received many a cease-and-desist order; in its later days, before Wizards of the Coast bought it out, it issued many of its own. Right from the start, entrepreneurial geeks looked at the amateur production values of the 1974 D&D booklets and decided that they, too, could put together a roleplaying game. To this day, some game designers actually criticize RPGs that intimidate amateur authors with their too-slick, too-professional products. RPG culture has always warred with itself about the business of making games, just as players debate how to run their game of D&D.

Gary, Dave and Aeschylus

Let’s go back to those Greeks for a moment. Back in their day, a stage play consisted of a single actor and a chorus. There was no drama as we know it, until the great playwright Aeschylus introduced a second actor who exchanged dialogue with the first. This innovation is what Jorge Luis Borges calls a moment of “modest history.” This wasn’t a war or a revolution or technological change or the meeting of civilizations. This was a subtler transformation. Aeschylus essentially invented acting, forever changing entertainment.

Dungeons & Dragons may mark a similar moment. When wargames shifted from history to fiction, from armies to individuals, when roleplaying became a means of collective creativity rather than a technique of therapy, we may have experienced a change that, just like the invention of drama, will affect humanity for thousands of years to come. The two crazy elements that made it impossible for anyone to invent D&D before Gygax and Arneson are precisely what will endure in media yet unknown to us. Just as acted dialogue is essential to movies and television, so a taste for chaos and a collaborative spirit will define the entertainment of the future.