In Other Waters was born in the turquoise waters of the Aegean.

It was 2017, and I was on the Greek peninsula of Kassandra, swimming in the Toroneos Gulf each day. Those glassy, turquoise waters have a long history of welcoming swimmers, and every year since 1971 the gulf sees hundreds crossing in a marathon from one arm of Halkidiki to the other. Its ecological history is far longer than that, however, and its clean and placid water has been a nursery for juvenile creatures for thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of years.

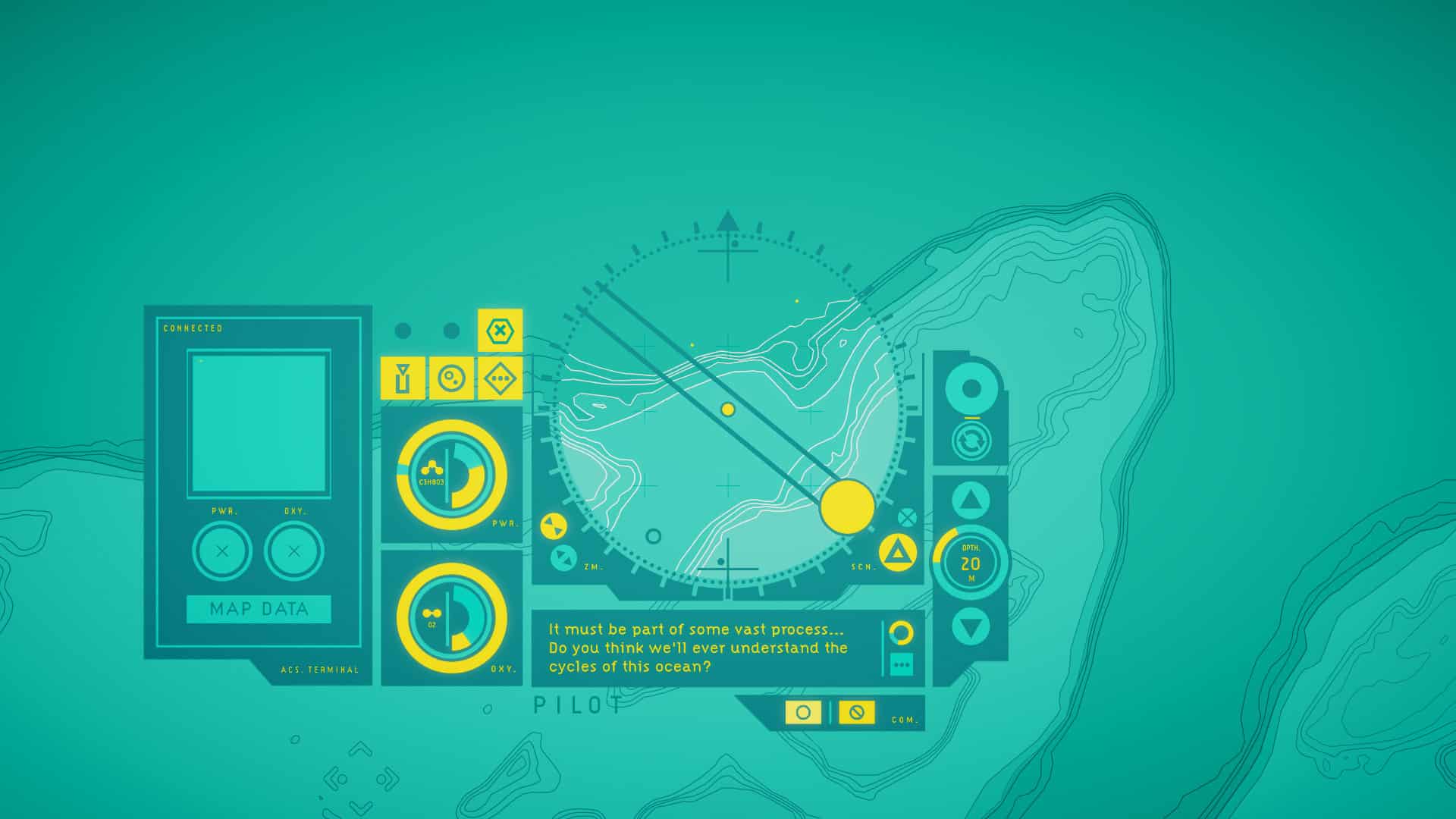

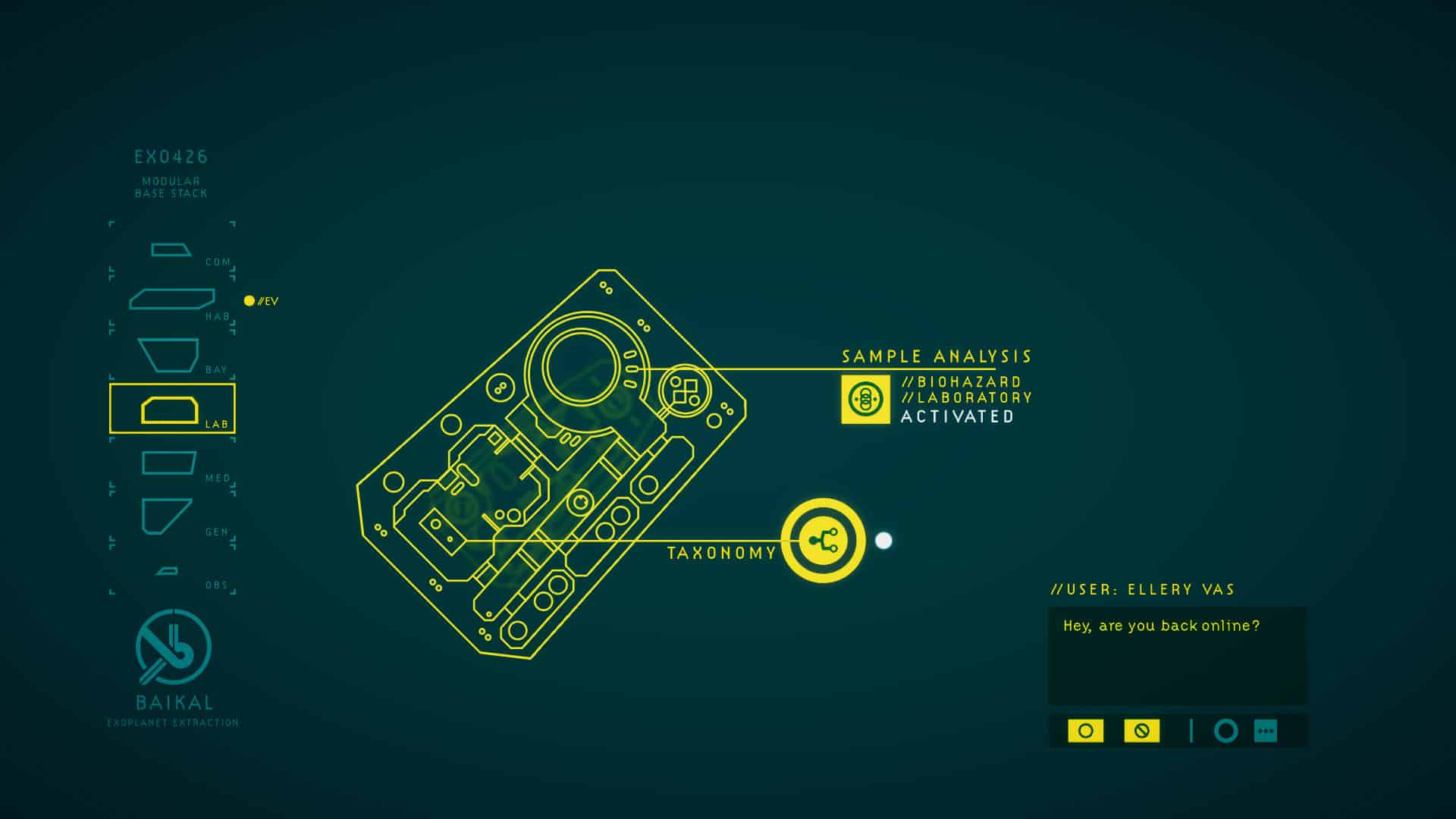

Swimming among them and encountering shimmering shoals of baby needlefish, a wandering salp that was like a transparent bag of organs, and a standoff with a barracuda imprinted the idea of a game about marine biology in my mind. That idea was fed through the lens of the science fiction I was reading at the time — the unnerving ecology of Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation and the mentally unraveling scientists of J.G Ballard’s The Drowned World — to become a game about a xenobiologist, disappearing into an alien ocean, with only a posthuman AI for company.

Two and a half years later, in the final stages of the game (sitting in my home office in a particularly rainy East London), it can be hard to fully remember the feelings imparted by those days of swimming and exploration. But despite their distance in time and atmosphere, I feel that they run as an undercurrent to everything that has happened since then.

At first the game felt like a shot in the dark. Not only did I manage to singlehandedly get it funded on Kickstarter with a prototype built in a few weeks, but I had a publisher on board, funding in place, and two years of guaranteed work ahead. I was, and continue to be, pleasantly surprised by the amount of people who got on board with the game’s slightly strange proposition. It’s a game where you study a world you never see, where you have a relationship with a character whose voice and face remain a mystery, and where you cannot simply push a stick to move in the right direction.

But perhaps one of my favorite things about this period of video games as a medium is the volume of people who are actively welcoming to experimental and original work. Coming from a background in theater and literature, where conventions are so well established that experimental work has to occupy a very small niche, I found this support for “the new” incredibly invigorating.

And in 2018 when the game was funded, invigorating was what I needed. Though I had almost a decade of work as a multidisciplinary designer when I started, shifting to an entirely self-motivated work schedule operating out of my own studio meant some serious adaptation. I quickly found that waking up every morning, looking two years into the future at the finished game, and then trying to figure out what I had to do today to get there was an impossible routine to keep up.

Instead I worked out ways of managing myself, as if I were simultaneously occupying many different roles in the studio. Using Notion software, I built a system that would display only today and tomorrow’s tasks, keeping my eyes firmly on each step in the process. As long as I kept my schedule up to date, then I could be sure that every morning I could wake up to a clear set of goals, set by my manager — my previous self.

This was my first taste of running a solo studio, and as the deadlines came and went, I got more and more proficient at creating structures for myself. Last year, when I traveled to Paris to receive Indiecade Europe’s Jury Prix, I gave a talk on the importance of “gaps” in games. Over the past two years those “gaps” have become the central ethos of both the creative and practical work in my studio. I suppose, if that seems confusing, you might think of my gaps as “frames” instead, empty spaces surrounded by a structure that makes it easier to fill in that space.

To give an example, each ecosystem of In Other Waters is really a series of frames. First I would start with the general conditions. Is the water oxygenated or toxic? Is there sunlight? What’s the geology, the currents, the weather? These would allow me to block out a set of concepts and leave them in place. If I then had to switch roles and spend a week or a month working with my composer Amos Roddy, or preparing a press demo, I could also come back knowing that the frame of each environment was waiting to help me fill it in. After all, certain conditions means certain creatures, and certain creatures means certain resources, and certain resources means certain gameplay elements, and so on down the chain of frames.

It was the same for my project management — I didn’t minutely plan my time. Instead I created flexible sets of work that gave me a prompt on what to do but allowed me to fill in the details. And if I ever got stuck, I could switch over to another task, leaving a gap that I could fill in later when I was ready. Even some of the game’s biggest plot points were just big question marks on Post-it Notes until I felt ready to finally work on them.

This kind of flexibility is one of the pleasures of being your own studio — you don’t need to do something before you want to, and if an idea just isn’t working, as long as there isn’t a deadline breathing down your neck, you can always give it time. There’s always something else that needs to be done. But keeping all of that information in your head can be a challenging process, and some days, I can’t remember if certain things are in the game or just in my mind. I will wake up in the middle of the night having mentally discovered a bug, or I might sit down to write out a section and find that it is already there. When you are playing all the roles at once, you sometimes lose track of which one of you is currently working.

Not that I managed to finish this game entirely on my own. My collaborators, chiefly Amos Roddy, the composer and sound designer for the game, and Chris Payne, a talented programmer who is an expert at fixing my mistakes, have been invaluable. Meanwhile, my publisher Fellow Traveller has provided backup when I needed it most, and my partner and daughter have been the reason I got up each day.

Working alone on a game can be a very internal process, and so much happens in your head each day despite your body barely moving from that office chair. Working with Amos and Chris often feels like a respite between the long stretches of solo dev, and I would encourage anyone in my position to make sure your collaborators are an entirely positive influence. When you are the studio, any kind of friction can delay the game and halt work, so making sure you have reliable backup is totally necessary. Any niggling doubt in a person’s support for the project will open up into a wound over time, and these things have a tendency to strike at the worst times.

Those times came during In Other Waters’ development, but now that I’m firmly on this far side of them, I feel like I am better prepared for when they come again in future. Occasionally, during development, I’ve thought about those swimmers of the Toroneos Gulf, crossing the 26 kilometers of open water between the two peninsulas. Stamina and focus are their obvious qualities, but I think the equally important, less spoken-about quality is knowing your limits.

I knew full well, despite the temptation of those waters, that I would never be able to swim the distance, and in the same sense, with In Other Waters I constantly reminded myself of the scope I was able to fulfill, not just the scope of which I was able to dream. One of the advantages I think I had in this process was a long period of freelancing in my past. I have delivered tens of large-scale projects in my time, some of them good, some of them bad, and through that process I lost the need for things to be perfect. Instead I learned how to get things “done” and move on. Keeping an eye on the scope of the game and adjusting it to fit the time I had was all in the service of this. This was a game that needed to fit my limits, not to test them to the breaking point, and with the game in the very final stages I take some satisfaction from having kept it within the scale I had.

But more than that, when all the practical considerations fade away, there are also occasional moments of playtesting where I recognize the game once more. An atmosphere or a moment takes me by surprise, and I am reminded of the turquoise waters, strange creatures, and imagined futures that set me on this path in the first place. Soon the game will be out of my hands and no longer something for me to hold onto, but something for you to experience instead. And I hope in some quiet moment, while you set a course within an alien landscape, you feel a little of something I felt back in 2017 too.