There can hardly be any dispute: Nvidia’s GeForce Now is cool. Instead of shelling out for a high-powered PC, you can rent a rig from Nvidia and play with the best of them via streaming. What’s not to like? A lot, apparently. GeForce Now is hemorrhaging publishers. Over the last month, many leading publishers — including Activision, Bethesda, 2K Games, Square Enix, and Capcom — have either removed their games from the service or refused to participate in the first place. The publishers have not offered much explanation as to why they’re leaving the service, but there’s a good chance it has to do with money.

On first glance, this might not make much sense. Why would Nvidia even need the publishers’ permission in the first place? If GeForce Now only lets people play games they already own, then what’s stopping Nvidia from ignoring the publishers and offering the games anyway? The publishers already made their money when they sold the game in the first place — why should users (or Nvidia) have to pay more money to access games they already own?

The answer has to do with the fact that you don’t actually own any of the games you purchase. Here’s how I explained it last year:

Contrary to popular belief, when you buy a video game you are not buying the game itself but are instead buying a license to play the game. The EULA (end-user license agreement) describes the license you purchased and outlines the limitations surrounding that license. When it comes to video games, most EULAs authorize individual, private use of the software and require consumers to use the game as intended.

Until recently, the distinction between owning a game and owning a license to play a game hasn’t really mattered. That’s because, until recently, licenses were essentially independent from the underlying game data, meaning that developers could not revoke access to a game once the game was distributed. As I explained last year, developers don’t have the ability to “enter (a) user’s home and remove (games) from their computer.”

GeForce Now changes the equation, since it allows users to access games that are stored on Nvidia’s computers, rather than their own. This leads to two questions:

- Do users need a special license to access their games on NVidia’s computers, or is that access allowed by the original EULA?

- Does NVidia need a license to stream games over GeForce Now?

Does GeForce Now Violate Users’ EULAs?

As one might expect, there is considerable variance in how license agreements are written, and that variance makes all the difference. For example, Konami’s EULAs grant users the right “to install and use one (1) copy of the Game Software” and prohibits users from using the game in a “remote access arrangement.” That agreement clearly considered and excluded the use of a service like GeForce Now. On the other hand, Activision’s EULAs grant users “a license to install and use the Software.” That agreement clearly does not exclude the user of a service like GeForce Now. Finally, there are EULAs that are somewhat ambiguous.

For example, the license agreement associated with Blizzard’s StarCraft II grants users a license to “install the Game on one or more computers owned by you or under your legitimate control.” The legitimacy of GeForce under that provision depends on whether a user has “legitimate control” over Nvidia’s computers when they start a GeForce session. On the one hand, the user decides what games to play and has complete control over in-game options and game configurations. On the other hand, users don’t have any meaningful control over the underlying computer. Thus, it’s hard to say one way or the other whether GeForce Now would be permissible under the Blizzard EULA.

While specific terms vary from agreement to agreement, my general impression is that most EULAs are like Activision’s and do not expressly prohibit a service like Nvidia GeForce.

Does Nvidia Need a License to Stream Games?

The question of whether Nvidia needs a license starts right where we left off. We all know that the Copyright Act makes it illegal to copy video game code, videos, or animations without permission — that’s why EULAs exist in the first place. What is not as well known is that it is illegal to facilitate others’ illegal copying. This means that it would be illegal for Nvidia to offer a service that would cause users to violate a license agreement.

From a practical perspective, that pretty much settles the question — Nvidia is required to obtain permission from any publisher whose EULAs exclude the GeForce Now service. But that’s not all. Publishers are not required to use the same license agreements for all eternity. Instead, publishers can revise their license agreements as they see fit. In particular, publishers like Activision can modify their standard EULAs to prohibit future purchasers from using their licenses to access games through GeForce.

In other words, the publishers hold all the cards — at least with respect to future sales. While Nvidia could disregard publishers’ preferences with respect to old licenses, that would likely damage Nvidia’s ongoing relationship with game publishers and make it harder for Nvidia to obtain publisher permission to host new games and newly purchased copies of old games.

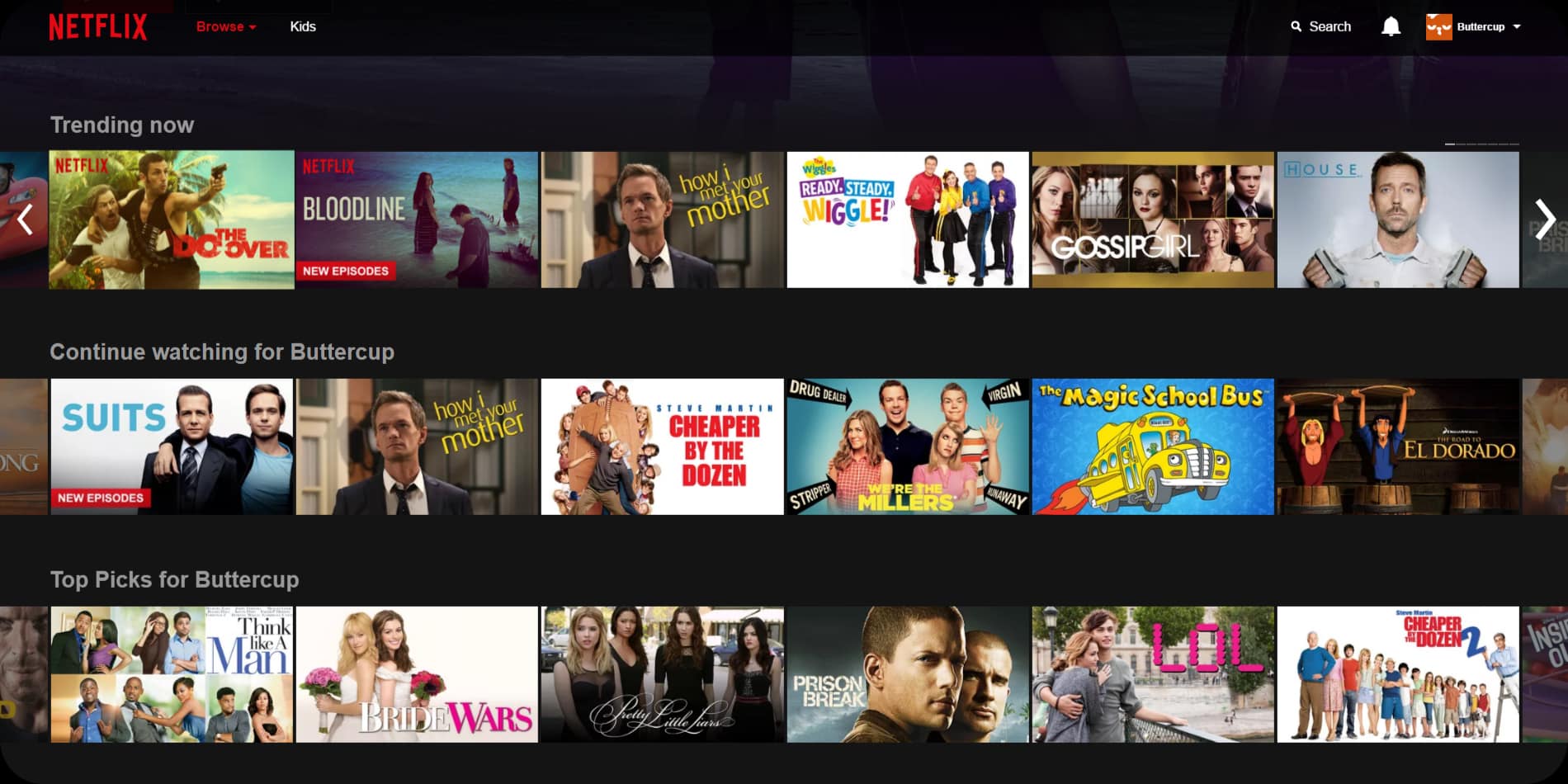

Notwithstanding the users’ license agreements, there’s another problem. It is also illegal to “publicly perform” a copyrighted work. While it’s a little counterintuitive, the term “publicly perform” can include private streaming. The question of whether a stream constitutes a public performance depends upon whether the underlying service is made available to the general public. This is why Netflix has to pay millions of dollars for each of its licensed shows — the fact that each user receives his or her own private stream from Netflix doesn’t change the fact that Netflix offers those private streams to everyone. For similar reasons, GeForce Now amounts to a public performance of video games, since any member of the public can use the service to access copyrighted video game content.

On the other hand, if GeForce Now simply allows users to rent rigs from Nvidia and grants users full control over those rigs for the duration of the rental, then it makes little sense to hold Nvidia responsible for anything — it cannot be said that Nvidia is making a public performance if the subscribers are calling all the shots. At first glance, this argument is compelling. Unfortunately, it doesn’t hold up — the argument was rejected by the United States Supreme Court, which considered the same question in the context of TV streaming.

In ABC v. Aereo, the Supreme Court considered the legality of Aereo, a startup that allowed subscribers to “rent” mini-antennas and to stream TV shows that were received from those antennas. ABC sued Aereo and argued that users’ ability to access broadcast TV on demand meant that Aereo publicly performed the copyrighted TV programs. The Supreme Court agreed. The fact that Aereo’s subscribers chose when to activate the antenna, which program to watch, and when to activate the stream made no difference. For similar reasons, users’ participation in GeForce Now are not likely to defeat a publisher’s claim that GeForce Now “publicly performs” copyrighted video game content.

GeForce Now is a remarkable service. While it’s not the first video game streaming service, it is the first to allow users to stream games they already own without making an additional purchase. The benefits for users are obvious — they can access the best versions of their games without worrying about hardware upgrades or frustrating system requirements. The downside for publishers is equally obvious — why let users access already purchased games when they can get users (or Nvidia) to purchase the games again? This wouldn’t be a problem, except for the discrepancy between what users think they purchased and what users actually purchased. Unfortunately, Nvidia got caught in the middle, and the realities of business, copyright law, and contract law mean it has no choice but to get the publishers on board — or die trying.