As with most things in life, it is perhaps easiest to explain the popular memory of Twin Peaks by referencing to The Simpsons.

In October 1997, more than six years after that spectacularly trippy final episode of Twin Peaks, The Simpsons broadcast “Lisa’s Sax,” which contained an extended flashback set in 1990. At one point, Homer is hunkered over on the couch watching a giant dance with a horse in a field beneath a set of swinging traffic lights. “Brilliant,” Homer mutters out loud, admiring the artfulness of this surreal television show. He then has a dim realization. “I have absolutely no idea what’s going on.” It’s a joke that distills so much of the cultural memory of Twin Peaks into 20 seconds.

When Twin Peaks arrived in April 1990, it was a genuine cultural phenomenon. Time television critic Richard Zoglin wrote that it was “like nothing you’ve seen in prime time — or on God’s earth.” The premiere of the soap opera murder mystery was the highest-rated TV movie of the season, earning ABC’s best Thursday ratings in four years. It immediately became a “water cooler” sensation.

Twin Peaks was the brainchild of David Lynch and Mark Frost, who had first met while working on a conspiracy thriller concerning the death of Marilyn Monroe. In hindsight, it seems strange that the zeitgeist should latch on to Lynch as intensely as it did. After all, Lynch is a notoriously esoteric storyteller who operates according to his own sensibilities and aesthetics.

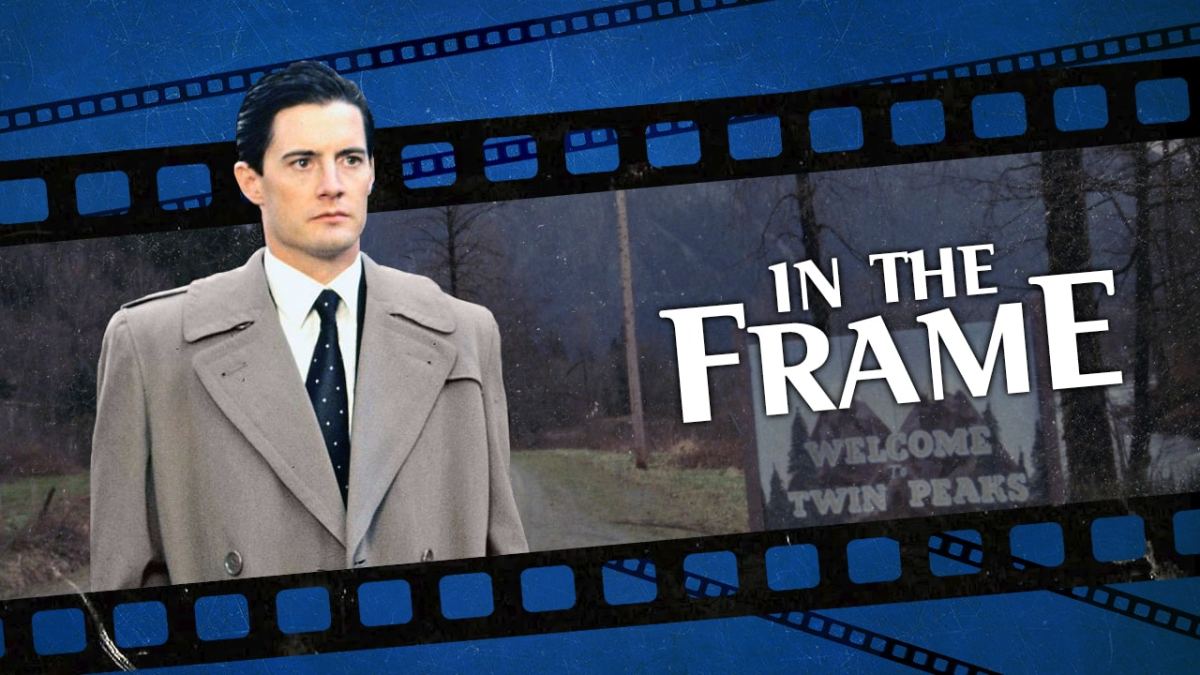

It helps that Twin Peaks has a seemingly straightforward hook into its more surreal elements. The series follows FBI Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) as he investigates the murder of homecoming queen Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) in the seemingly idyllic Washington town of Twin Peaks. However, Cooper quickly discovers something rotten beneath that polished exterior.

Despite that simple hook, Twin Peaks swerved rather sharply into the absurd. Twin Peaks existed at a point of intersection between soap opera conventions and Lynch’s unique directorial style. Time and memory have flattened this weirdness into something resembling “quirk,” but the truth is that Twin Peaks looked like nothing on television to that point.

The more obviously eccentric aspects of Twin Peaks, like “the Red Room,” the Man from Another Place (Michael Anderson) or the Giant (Carel Struycken), have been absorbed by cultural osmosis. However, these more cartoonish elements don’t completely capture the weirdness of the series, which included extended sequences of characters dancing or traffic lights swaying.

Naturally, this approach alienated that huge audience. When Twin Peaks returned for its second season, ratings fell sharply. Lynch had wanted to leave the murder mystery at the center of the show open-ended, but ABC forced Lynch to reveal the killer nine episodes into the season. This drove a wedge between Lynch and the network, and ratings continued to plummet. The show was canceled.

There’s a common argument that Lynch’s films and television shows are “difficult,” that they are hard to decipher. That sentiment is perhaps best expressed in the two extremes of Homer Simpson’s reaction to Twin Peaks – that it is simultaneously brilliant and completely incomprehensible. The same logic might apply to Mulholland Drive or Inland Empire.

This perception of Lynch is rooted in a misunderstanding of his work. It treats his output as something equivalent to a “mystery box,” as if there is a clear and simple explanation that will allow everything to just click into place. After all, there has been a lot of digital ink spilled on the internal mythology of Twin Peaks, trying to parse it in a manner similar to Lost or The X-Files.

While it’s fun to break down the symbolism of Lynch’s work, there’s rarely a right answer. The logic that drives his work is not absolute. “Very rarely have I gotten ideas from nighttime dreams, but I love dream logic,” he explained. Many of the surreal elements of his work are drawn specifically from Lynch’s own life. The images mean something to him, but that meaning is not universal.

Lynch has explained some of his inspirations. The idea of the iconic “Red Room” apparently came to him when he was leaning against a hot car one day. “My hands were on the roof and the metal was very hot,” he recalled. “The Red Room scene leapt into my mind. ‘Little Mike’ was there, and he was speaking backwards … For the rest of the night I thought only about the Red Room.”

Similarly, the monstrous “frogmoth” that appears in the eighth episode of Twin Peaks: The Return has been the subject of a lot of speculation and thematic discussion. Is it a manifestation of evil and corruption? Is it an allusion to biblical plagues of frogs and locusts? Maybe, but it’s also drawn from a very specific and personal memory for Lynch of a trip he took to Europe with his brother Jack.

This is not to suggest that Lynch is a purely autobiographical filmmaker. He has pushed back against the idea that the darkness in his work reflects some deep-rooted personal trauma. “You know, a lot of times when people say these things, they’re really talking about themselves,” he stated. Mel Brooks, who produced The Elephant Man, described Lynch as “Jimmy Stewart from Mars.”

Lynch’s idiosyncrasies push back against a lot of the tools of contemporary critical discourse. Noel Murray has discussed the challenges of “recapping” The Return, and Matt Zoller Seitz acknowledged the folly of trying “to turn an essentially left-brained work of art into a right-brained one.” Lynch often seems more interested in expressing himself than explaining himself.

This is what makes Lynch’s work so fascinating to some and so alienating to others. Personally, I’ve always found that I respond to Lynch’s work emotionally rather than intellectually. I feel Lynch’s works more than I necessarily comprehend them. This is perhaps why Lynch’s sensibility is so hard to even articulate, with the adjective “Lynchian” overused to the point that it is a synonym for “weird.”

This is the beauty of Lynch’s work. Ten people can watch the same work and come away with 10 wildly divergent opinions, knowing that there is no single right answer against which they might measure their own interpretation. The author may not be dead, but he is perhaps on another planet. There is an internal logic holding it together, but it is often obscured from casual observers.

This gets at the real horror of Twin Peaks. In a mundane sense, the audience can comprehend Laura Palmer’s tale of sexual abuse, incest, drug addiction, prostitution, and corruption. Intellectually, as accurately as those descriptions might explain what happened to Laura, they don’t capture the real nightmare of Laura’s experience, particularly in the context of prime-time network television.

Watching Twin Peaks forces the audience to feel that horror. This is something more primal and more unsettling, a fundamental wrongness that cannot be neatly explained. Lynch was right; the mystery at the center of Twin Peaks cannot be meaningfully solved, because solving it implies closure or resolution. Emotionally, the death of Laura is a wound in the skin of the world.

If it were possible to fully articulate the extent of that wound, to map its contours in language and set its boundaries in words, then we might hope to treat it. If the inhabitants of “the Red Room” could be neatly catalogued, they would become less horrifying. Twin Peaks repeatedly suggests that there are rules that guide and shape the chaos of the world around its characters, but those rules are unknowable to both them and the audience.

Actor Ray Wise once suggested of Lynch that “his take on life is weird because life is weird.” Very few directors capture that weirdness as well as Lynch, and very few shows as effectively as Twin Peaks.