Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy remains a rare accomplishment in blockbuster cinema, and it stands quite apart from most of the superhero mega-franchises around it.

The superhero is a distinctly American figure. “Is there any character archetype as quintessentially American as the superhero?” asked Eileen Gonzalez in Book Riot. “The superhero comic is the American dream illustrated,” contended Umapagan Ampikaipakan in The Washington Post. Author Anna Peppard places the superhero as an evolution of the classic frontier myth, evoking “enduring notions of American heroism as supremely individualistic, stoic, and, of course, superheroic.”

This individualism is central to the classic superhero myth and a key feature of American storytelling. As Elias Isquith noted, the default mode of crowd-pleasing Hollywood storytelling is that “[i]t’s individuals, and individuals alone, who matter.” Superhero films are often power fantasies, stories of truly exceptional people who often operate with a minimum of oversight or consequence. Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy exists in conversation with that portrayal.

In every incarnation, Batman is obviously an exceptional individual. Billionaire Bruce Wayne was so traumatized by the death of his parents that he decided to wage a one-man war on crime. In his classic comic book origin, Bruce becomes a “master scientist” who “trains his body to physical perfection.” He builds “wonderful toys” and raises a “family” of bat-themed superheroes around him that accept his branding, often treated as “soldiers” in his war.

In recent years, Batman has become an avatar for broader critiques of the superhero as an archetype. It has become a cliché to suggest it would be more constructive for Bruce to donate his fortune to charity rather than to funnel it into his war on crime. These criticisms have even been folded into media itself. The trailer for Blue Beetle includes a line about how “Batman is a fascist.” Batman has become a lightning rod for these debates about the genre.

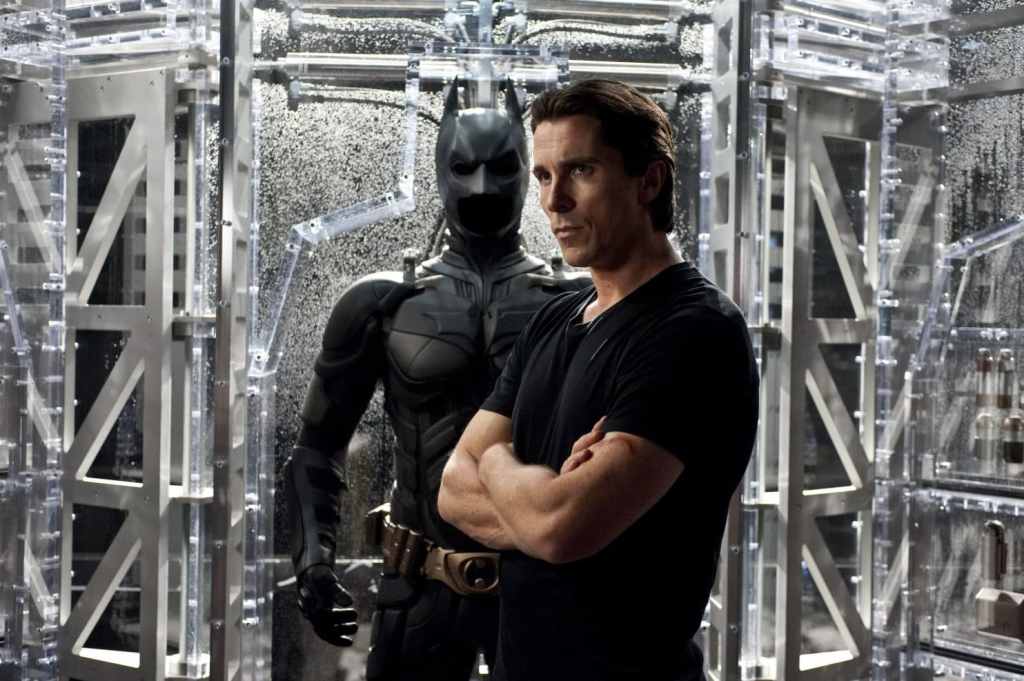

In this sense, Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy was ahead of the curve. The three movies are ambivalent about the hero at their center. In particular, the films are extremely wary of Bruce’s (Christian Bale) efforts to concentrate power in himself as an individual. This is obvious from Batman Begins, but it builds through The Dark Knight and into The Dark Knight Rises. The trilogy is deeply concerned by the notion of a billionaire taking this power unto himself.

The films ask why Bruce Wayne holds the moral authority to operate as “a vigilante who spends his nights beating criminals to a pulp with his bare hands.” Early in The Dark Knight, a low-rent vigilante (Andy Luther) inspired by the Caped Crusader challenges him, “What gives you the right? What’s the difference between you and me?” Bruce replies, “I’m not wearing hockey pads!” It’s not a convincing argument, and the films know this.

When Bruce describes him as a vigilante in Batman Begins, Henri Ducard (Liam Neeson) responds, “A vigilante is just a man lost in the scramble for his own gratification.” Ducard instructs Bruce to “make (himself) more than just a man.” At the climax of The Dark Knight, Bruce reveals that he has turned every phone in Gotham into a microphone. “This is wrong,” gasps Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman). “This is too much power for one person.”

The Dark Knight trilogy is aware of the allure of the myth of the exceptional individual. “When their enemies were at the gates, the Romans would suspend democracy and appoint one man to protect the city,” Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) explains in The Dark Knight. “It wasn’t considered an honor; it was a public service.” His fiancée, Rachel Dawes (Maggie Gyllenhaal) retorts, “Harvey, the last man that they appointed to protect the Republic was named Caesar, and he never gave up his power.”

Bruce is seduced by Harvey. The district attorney presents himself as a charismatic leader, one who plays by his own rules and can “make (his) own luck.” At times, Harvey recalls an old-fashioned frontier lawman. He punches out a witness on the stand, then asks to resume questioning. Bruce comes to believe that Harvey might be able to replace him as “Gotham’s White Knight,” even throwing him a fundraiser. However, Harvey is ultimately corrupted.

In The Dark Knight Rises, Bane’s reputation is built on the myth that he was the only person to pull himself from the pit. This is a lie; it was Talia Al Ghul (Joey King, Marion Cotillard) who escaped. Bruce defeats Bane at the climax by smashing his mask. It is a tactical choice, as the mask provides the painkillers that allow Bane to function; as with Bruce, “the mask holds the pain at bay.” However, the destruction of the mask is also symbolic. It’s the destruction of a myth.

Throughout Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, it is clear that Batman is the product of more than one man. Bruce originated the idea and wears the mask, but Batman cannot exist without the support of a larger body of people. As with Nolan’s work on Inception, this could be read as a metaphor for film production, an interrogation of the myth of the auteur. Nolan himself has a reputation as an auteur, but he also understands the importance of collaboration.

Bruce relies on other characters to make Batman a reality. His faithful butler, Alfred Pennyworth (Michael Caine), helps map the caves beneath his mansion and design a costume. Lucius Fox provides a wide range of cutting-edge technology that Bruce would never engineer himself. At the climax of Batman Begins, Bruce ends up putting Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman) behind the wheel of the Batmobile. Even practically, Bruce cannot do it alone.

More than that, these characters serve as a system of checks and balances on Bruce. They lend him moral authority. Jim Gordon is the only good cop in a corrupt department, and his embrace of Bruce grants the project some legitimacy. Alfred calls out Bruce’s “thrill-seeking” behavior in Batman Begins. In The Dark Knight, Lucius responds to Bruce’s invasion of the city’s privacy by leveraging the threat of his resignation. Batman is a group effort.

Even with this system in place, this power is still too concentrated. It taints those it touches. By The Dark Knight Rises, Gordon’s compromises have left the once-heroic cop a shell of his former self; his wife has left him and his career is in decline. When he rants about how Bruce did terrible things so that he could keep his own hands clean, John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) replies, “Your hands look plenty filthy to me, Commissioner.”

Bruce becomes so consumed by Batman that he drives Alfred away. Calling out Bruce’s reckless antics, Alfred offers his resignation. “Leaving is all I have to make you understand,” Alfred explains, recalling Fox’s threat to resign over the invasion of privacy in The Dark Knight. While Fox convinced Bruce to destroy that device, Alfred can’t talk Bruce out of his self-destructive confrontation with Bane. Bruce still gets “lost inside this monster.”

The Dark Knight Rises ultimately goes further, suggesting that the idea of that masked billionaire vigilante is inherently flawed. Asking how Talia pulled herself up from the pit, Bruce is told that she could ascend because she was “a child born in hell” rather than “a child from privilege.” Bruce finally donates his one remaining significant asset, his house, to the city’s disadvantaged. The film also ends with John Blake becoming Batman, a working-class orphan with a history of public service rather than a billionaire socialite.

This is an approach to the idea of superheroism that exists at odds with the current blockbuster template. There is a staggering lack of ordinary people within these modern gigantic shared universes. In most of these films, the only people that superheroes hang out with are other superheroes. When ordinary people exist within these superheroic social circles, they are often just superheroes-in-waiting, hoping for their own shot at the spotlight.

Captain America’s (Chris Evans) best friend Bucky Barnes (Sebastian Stan) becomes the Winter Soldier, and his new pal Sam Wilson (Anthony Mackie) is the Falcon. Iron Man’s (Robert Downey Jr.) best buddy Rhodey (Don Cheadle) gets his own suit of armor, as does his girlfriend Pepper Potts (Gwyneth Paltrow). Ant-Man’s (Paul Rudd) friend Luis (Michael Peña) and ex-wife Maggie (Judy Greer) disappear between movies while his daughter Cassie (Kathryn Newton) becomes a superhero.

There is no room for characters like James Gordon, Alfred Pennyworth, or Lucius Fox within modern mainstream superhero blockbusters, characters who have their own stake in Batman. Nolan stands apart from many superhero filmmakers by interrogating the myth of the rugged individualist. Many of Nolan’s movies are rejections of the self-made mythology of great men: Leonard (Guy Pearce) in Memento, Dormer (Al Pacino) in Insomnia, Mann (Matt Damon) in Interstellar, Borden (Bale) and Angier (Hugh Jackman) in The Prestige.

In contrast, Nolan’s movies favor collectivism and group action. Dunkirk is a war film without movie stars, populated by characters that are often anonymous, in which individual threads are consciously less than the larger collective. For Nolan, Dunkirk is a movie about “communal heroism.” In Nolan’s own words, Dunkirk is about “the idea of community, what we can achieve together, as opposed to this cult of individuality that we live in right now.”

“It’s become very fashionable in the last couple of decades to forget what good government can do, what good union organizing can do,” Nolan argued in the lead up to the release of Dunkirk. “The idea that benevolent capitalists will just take care of us and the people on top will magically distribute wealth and happiness and security to us little people… no. It’s time we wised up.” This is at odds with the tendency in certain critical circles to argue that Nolan is “the last Tory” who makes movies with a “reactionary sentiment.”

This has become clear during the current Hollywood labor strike. Nolan correctly pointed out how the shift to streaming would hurt below-the-line staff. He is one of the few major writer-directors to picket with the WGA, and he voiced support for his cast’s decision to leave the Oppenheimer premiere in solidarity with the SAG-AFTRA strike. This is reflected in Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy and is one reason why they stand as a towering accomplishment within the genre. They’re thoughtfully engaged with what a superhero actually is.

Like the rest of Nolan’s filmography, these three movies are about the dangers of exceptional men lost in pursuit of their own greatness, as well as a reminder that progress is a collective endeavor. They’re a deconstruction of the individualist myth of the American superhero and an attempt to build a better Batman.

Published: Jul 15, 2023 12:00 pm