With the possible exception of the Max Payne remakes, I can’t think of a single major “sad dad” game on the horizon. Maybe that’s a good thing. As great as Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead, The Last of Us, and God of War are, they’re quite limited in how they use journey narratives and mostly conventional gameplay (or gameplay that has since become conventional) to explore the theme of parenthood. But I wonder if their decline makes way for the rise of something both similar and different. In the past few weeks, I’ve come across three games that remove the sad dad from the center of the experience and place the missing mother there instead.

One of them, Venba by Visai Games, was just a demo, so it’s hard to say the influence that element will have across the full game when it launches next week. The protagonist, Venba, is struggling to build a new life in a new country. There’s no support network for her, and so, in a time of difficulty, she leans on the only thing she has left. Venba’s missing mother is present in the game through a battered recipe book, which she turns to for comfort in a time of crisis. In this, the game seems to apply a familiar sentiment of motherhood, that of protector, of salve, of someone you can rely on, even if only in memoriam. This single example shows a shift in the contexts of parenthood. There’s none of the teething issues or problematic intergenerational relationships that are so bound up in sad dad games.

However, that’s just one characterization. Released at the end of May, Miasma Chronicles from The Bearded Ladies offers another. In it, we assume the role of Elvis, and his story begins with his trying to break through a wall of Miasma to reach his mother, Bha Mahdi. This missing mother appears almost as a mythical figure. Bha Mahdi is a warrior-witch, holding back the forces of darkness that threaten to consume the town of Sedentary, just as they have consumed the lost, mythologized America. Her absence is willful — it is, in fact, a test for Elvis — but she’s seen to be called to some kind of higher purpose. She remains aspirational, for Elvis and the people of Sedentary alike, rather than a figure whose absence is monstrous. And when Elvis does eventually, inevitably, find her again, it’s alongside revelation. She morphs into a guide and guardian, an embodiment of the Wise Woman archetype.

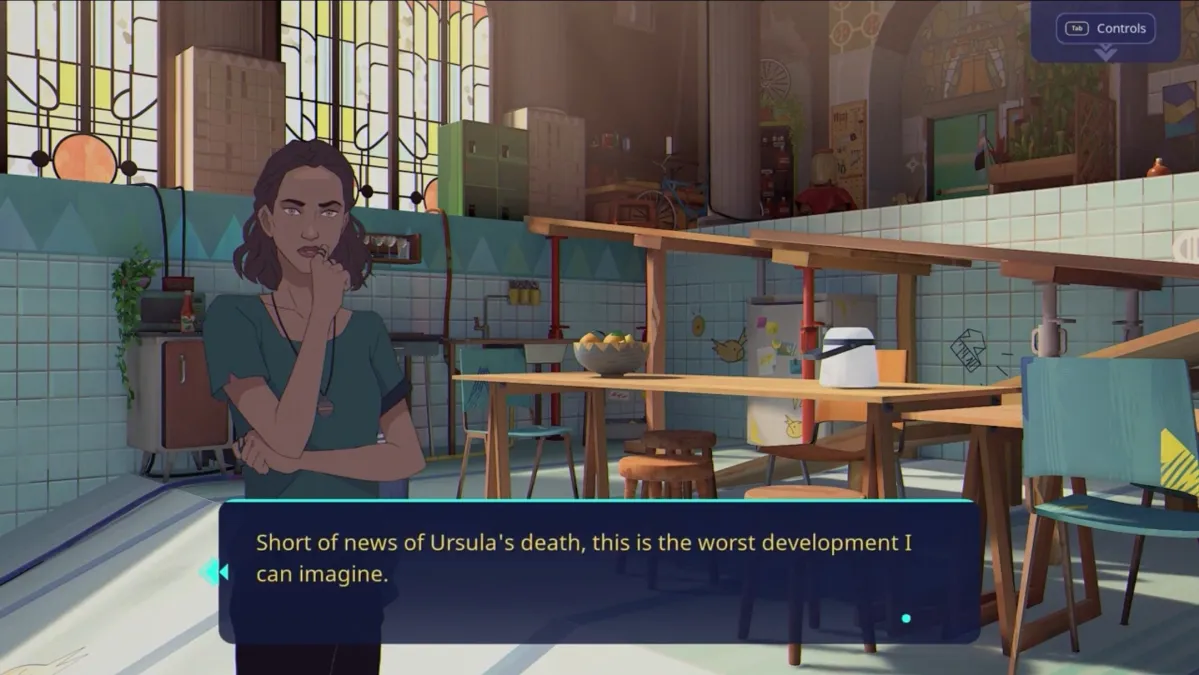

The other game that inspired these reflections is Don’t Nod’s latest, Harmony: The Fall of Reverie. Again, the missing mother is the inciting incident, resulting in protagonist Polly returning to her hometown and finding it not as she remembers. The disappearance of Polly’s mother, Ursula, is unlike those of the two mentioned above in that it’s a complete mystery. No one knows where she went, so Polly’s quest to find her is based around investigation in both the “real” world and mythical realm of Reverie. For much of the game, that search is the driving force, and it’s bound up in complexity. Polly feels duty bound to find Ursula, even while she knows that finding her will be a bittersweet occasion due to their fraught relationship.

Across these three stories, then, we see three different types of parent-child dynamics. They each speak to shared histories, which enables the characterization of the relationships to run deeper than those explored in the likes of Telltale’s The Walking Dead or God of War. Where the journeys of Lee & Clementine, Kratos & Atreus, and Joel & Ellie were exercises in bonding, this new crop is about exploring the complexities that stem from feelings of abandonment, uncertainty, absence — balanced alongside the more positive associations of family: safety, familiarity, assurance.

Coincidentally, I’ve recently read A Vindication of Monsters, a book of essays about Frankenstein author Mary Shelley and her feminist pioneer mother Mary Wollstonecraft. In her contribution, the book’s editor Claire Fitzpatrick writes that absent parents work in fiction to prompt protagonists to solve problems, long for success, embark on journeys, or seek revenge. “Absent parents are usually used as a way to create drama and emotion,” she writes. Certainly, that’s true in Venba, Miasma Chronicles, and Harmony: The Fall of Reverie, but it’s also true of Frankenstein.

Mary Wollstonecraft (left) and Mary Shelley (right). Image via Fortuna Ventures Limited.

For context, Wollstonecraft passed away as a result of complications from childbirth after 11 days, and young Mary grew up the daughter of a distant stepmother while idolizing the legacy and work of her biological mother. I mention that because that background bled into Frankenstein. The book is frequently viewed as a metaphor for parenthood, with Victor being a negligent mother figure, abandoning his child — the Creature — after giving it life through his labors, and the troubled relationship that stems from his neglect. All of that is to say that this theme isn’t new; it can, in fact, be traced back to the very first science fiction story, now more than 200 years old.

But it still resonates and still gets deployed in ways that can surprise or at least give important context to the stories that it forms part of. In just the past few years, I’ve come across the absent mother (in each case dead, but no less absent) in R. F. Kuang’s Babel, where the death of Robin Swift’s mother is the catalyst that sees him snatched away to a fantastical version of colonial-era England; Andrea G. Stewart’s The Drowning Empire series, where the absence of protagonist Lin’s mother casts a long shadow over Lin’s identity; and V. E. Schwab’s Gallant, which begins in an orphanage and follows a daughter piecing together a haunted family history. They’re causes, objectives, and so much more because each protagonist’s response to the absence helps to define their character — much more so than yet another grumpy father trying to understand how to raise a child.

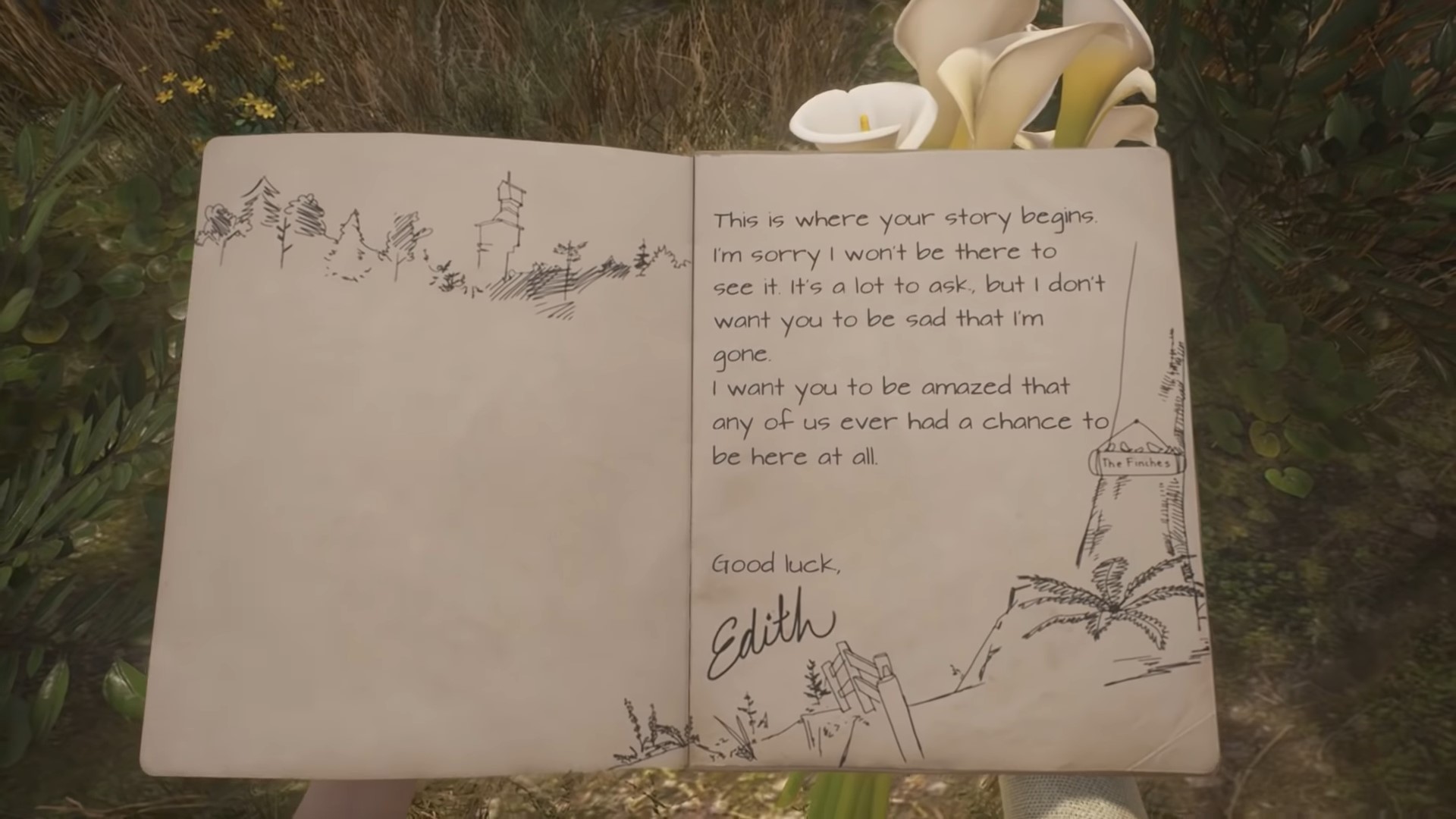

Nowhere has that already been so firmly established in video games as in What Remains of Edith Finch. The game is based around a teenage Edith coming to terms with her “cursed” family history. She peels back the layers, learning of her family by the things left behind, and then she, of course, passes that troubled legacy on to her own child at the end.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about all this is that sad dads and missing mothers are little more than different framing. It’s moving the attention from the father to the child. After all, God of War tells of a journey spurred by the passing of Faye — the mother figure — and while we see Atreus struggling with that, the focus is firmly on Kratos. Similarly, neither Telltale’s The Walking Dead nor The Last of Us ever really interrogates the absence of the original parents of Clementine or Ellie, instead focusing on the newfound relationships with Lee and Joel, respectively. Meanwhile, the likes of Heavy Rain, The Evil Within 2, Dishonored, and Red Dead Redemption exclusively center the father’s experience — predominantly within frameworks of violence, revenge, or desperation.

To be sure, there’s no reason that a mother or child can’t be driven by those same motivations to the same ends. But we don’t see that very often. Instead, stories of missing mothers tend to be more introspective, more explorative, and more varied. I know Lee is torn by his past actions and driven by a desire to protect Clementine, but I never felt like I knew him as a person. And I feel similarly about other sad dads, whereas I feel like I know Polly better because her history informs her relationships with other characters and the choices I make as her much more deeply.

Maybe that’s ultimately down to nothing more than narrative context. After all, Lee (and Joel) exists in a violent, post-apocalyptic world, and Kratos exists in a violent, pre-modern world. In contrast, Polly’s world is near-future, reflecting more cleanly the world we live in, making it easier to map her (and Ursula) to recognizable situations and wants and needs. But it’s similar, if not quite as potent, in the post-apocalyptic Miasma Chronicles. Elvis is trying to work out who he is, and Bha Mahdi, herself aloof yet insistent, is just one of the prisms through which he seeks an understanding of self.

So, maybe it’s more than the tropes that are being deployed, or maybe it’s just that video game storytelling continues to evolve over time and sad dads belong to a bygone era. Whatever the reason, the outcomes are clear. These missing mother stories tap into a richer vein of characterization. There’s more to our protagonists and their supporting casts than their roles as parents and children. And maybe the trope is nothing more than a flash in the pan, but there are still valuable lessons for future game narratives to draw from them.

Published: Jul 30, 2023 11:00 am