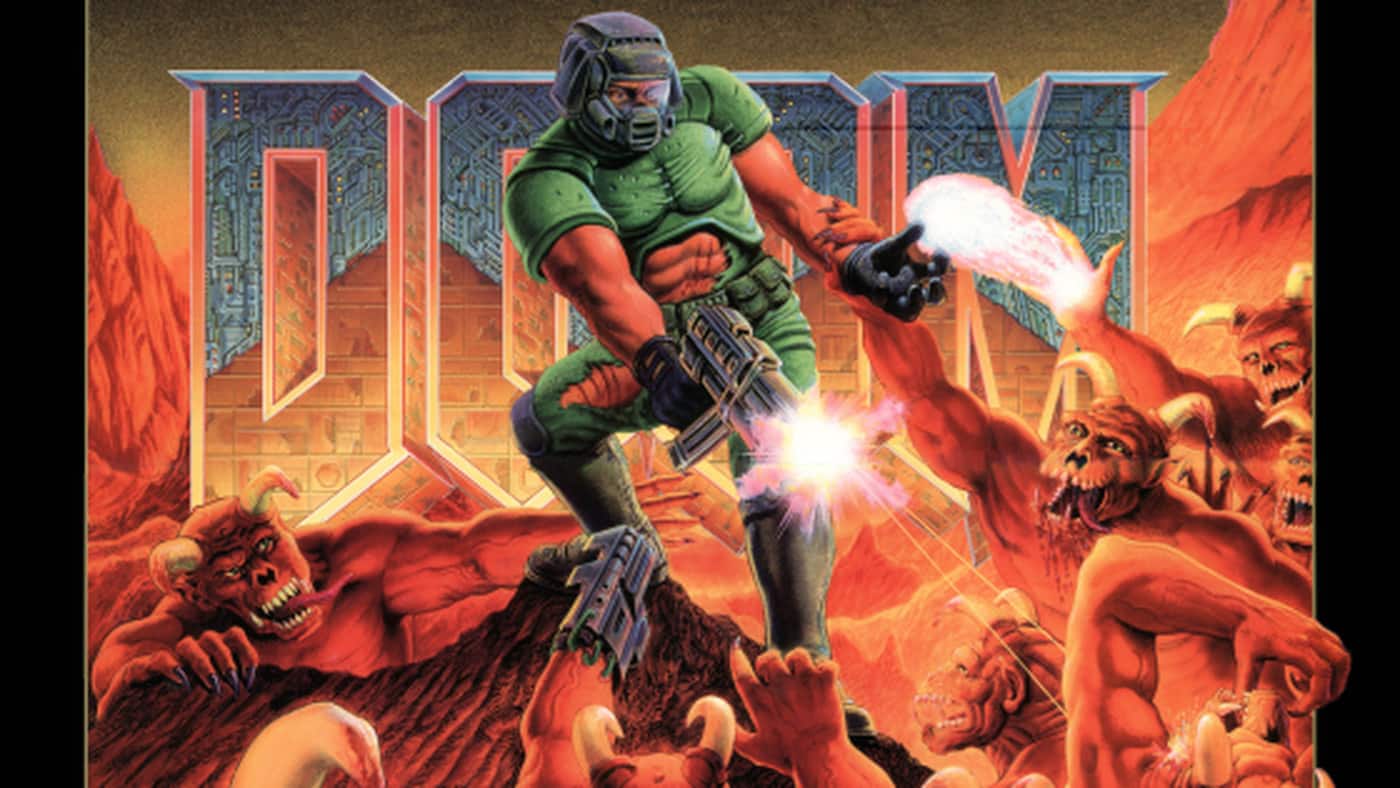

“If only you could talk to these creatures, then perhaps you could try and make friends with them, form alliances… Now that would be interesting.”

Edge magazine’s 1994 review of Doom remains the infamous catalyst for one of gaming’s most time-honored memes. Yet it also stands as a monument to the desire many find in game narrative, the desire to experience something beyond the binary of simple good and evil.

As games have become more mature, so too have the players of games. Good versus evil has just as much a place in game narrative as not; however, spoon-feeding didactic lessons is not the only way to tell a story concerned with morality, and exploring the nuances of what it means to be “good” or “bad” is just as relevant to the moral lesson of a game as the lesson itself.

Exploring Black-and-White Morality Through Gray Characters and Stories

In a recent Polygon article, author Khee Hoon Chan posits that all stories are inherently moral and, due to current unrest in real life, more games should commit to a morally black-and-white narrative “centered around the concept of absolute, objective morality.” I don’t immediately disagree with the assertion that stories are often moral — I believe that all entertainment has the potential to be morally significant outside the medium in which it is presented. If storytelling is done well, it should make you consider the way you interact with the world around you. And if a character is created well, you should be able to identify elements of yourself in them. But a character does not need to be an infallible beacon of virtue to be “good” — and doesn’t have to be a Palpatine-esque caricature of unflinching malevolence in order to be “bad.”

Morality is not an absolute truth, scientifically derived absent all context. Each of us has hundreds of “lines” we do not cross in our lives, individually and legally imposed barriers that keep us firmly walking on our own individual moral paths. Video games give us the distinct ability to engage with our lines meaningfully — where they are drawn, the specific exceptions that might present themselves that would result in us crossing one of those lines, and the consequences of allowing such exceptions to alter our individual moral journeys. However, just as games allow us to consider our own morality, they also give us the opportunity to escape from it, to live outside our lines altogether. And that’s okay.

“Protagonist and antagonist” is not immediately synonymous with “hero and villain.” The protagonist is the character assumed by the player in a game, the one who drives the story forward, and the antagonist is any person or force who stands in opposition to the protagonist, the one who drives the plot forward.

Flawed, imperfect protagonists have a critical lesson to teach — the lesson that one need not maintain perfection in order to be considered good. Goodness does not have to mean your character is infallible. Much of the discovery and growth of the character comes from how they navigate their own shortcomings — and how those shortcomings are used to drive the character forward. Your character does not need to be saintly to be “good,” and the choices your character makes do not need to be easy or leave you feeling warm and fuzzy to be morally justifiable. It is possible — and often fascinating — to view the agent independent of their actions.

Sympathetic antagonists allow us writers — and by extension, players — to explore the evils of the world beyond the caricature. This is not done in order to make the actions or the character themselves sympathetic, but rather to discover the journey that led them to make the choice to be bad — and to identify the alternative choices available to them. In doing so, this gives the player the opportunity to contemplate the decision they may have made and to consider how the events of their own lives have shaped them. This underscores the notion that we are shaped by our experiences, for good or for bad, and highlights the importance of empathy, compassion, and understanding for the individual, even if not for the actions of said individual.

Gray characters, alternately, are characters that are not overwhelmingly good or overwhelmingly bad. They’re not quite villains, but they’re too twisted to be stereotypical heroes. One of the greatest benefits to writing morally gray characters is that they are truly unpredictable. Their motivations are not boiled down to “being good” or “being evil.” They are driven by a force, a goal, that exists on a realm outside the constraints of simplistic morality.

When you write a morally gray character, you are writing a protagonist or an antagonist, not a hero or a villain. They might do good things for bad reasons or in bad ways, or they might do evil things for good reasons. They might do both. Having a gray character does not equate to having a character without a moral lesson, but rather it is about having a character with a complicated moral lesson, one that is open to interpretation and discussion and, potentially, is different for each player. Games don’t require moral tutorials in order to be morally impactful.

In video games, gameplay is about creating opportunities that allow the player to leave their mark on the game’s world. Narrative, on the other hand, is about creating a story that allows the game’s world to leave its mark on the player.

Legends of Aria

On a small island off the western coast of the lush mainland, linking arms with the vast, barren desert, rests a magical altar. Emblazoned with the glowing letters of an ancient language, the stone serves as the peak of a lost temple, buried under a century’s worth of aureate sands. The high priestess of the monument had once conducted rituals upon the exposed platform, and few of the men and women of the land who petitioned her walked away from doing so. The entrance to the temple has long been sealed, with the fierce priestess trapped within.

So… who was she?

When I began writing for Legends of Aria, the game itself was already quite established with very little story. This is an atypical way of writing, and I spent a significant amount of time exploring the game’s world, studying the oddities that made it up, and working through different stories that could explain the existence of these oddities.

Storytelling in a sandbox MMO is unlike any other type of storytelling. Other stories typically have a clearly defined beginning, middle, and end, and writers have the benefit of building a narrative centered on a character whose motives they have some degree of control over. Each story is able to be crafted to test these motives while staggering it through a fairly linear series of events.

In Legends of Aria, I had to determine the stories I wanted to tell as well as the distribution of these stories. I decided to focus much of my time on fleshing out the history of the world, crafting tales of historical figures who, through their combined effort, shaped the landscape of the world the players would interact with.

So… who was she?

When I write any story, or any individual character, I find myself assuming the role of a petulant child, constantly badgering their mother with a never-ending strain of that dreaded question. “Why?” Why, for example, was this woman the leader of a misogynistic, cannibalistic, irrefutably morally black cult known for sacrificing human life to imagined gods? And why did they allow her to become that, despite their hard-wired hatred of women?

I told Sibilla’s story through a series of in-game tomes, collectible books that could be discovered at the whims of the player. One detailed her position within the cult, establishing her as a fearsome, objectively evil character. Another was a personal diary, hidden in the game and written by her when she was a child, detailing the hell that she endured through her young life. Another didn’t even mention her by name, but rather hid her origin deep in a completely separate story about a completely separate character. But — if a player was paying close enough attention — they would put together the pieces of the puzzle that would outline the tragedy that was this character’s life, as well as the heartbreaking motivation behind her actions.

It would be simple to answer the initial “Why” with “Because she is evil.” That she had been born as such and could never be more than that. That for true evil there is no choice. These are valid answers, but they leave little to be discovered. Sibilla’s origin does not excuse the evil she’s done – but it does explain it.

Trusting Yourself and Trusting the Player

Writing a story like Sibilla’s is about considering the player’s emotional experience. I determined different emotional rewards that I intended the player to take away from engaging with each individual piece of the story. Due to the nature of the game and my inability to control the order in which players would happen upon a piece of Sibilla’s story, I also had to make sure that every piece, and every emotional reward, flowed into another in a meaningful way regardless of the order. The most impactful way to do this was to have a solid end to her story and to give just enough explanation in the other pieces to allow the player to suppose the rest. I had to trust myself enough to scatter the breadcrumbs, and I had to trust the players enough to follow them.

It’s easy for writers to fall into the trap of over-explaining, to get so heavy-handed when we have a specific point we want to get across that we jump from storytelling to explicitly preaching. But we have to write with our audience at the forefront of our minds. If my game is geared towards a more mature audience, I can incorporate more mature stories, ones that don’t require me to explain every minute detail, but rather to lay it out and trust the intelligence of the players to put the pieces together for themselves.

Gray characters, ones with a much less clearly defined moral code, allow players to insert a piece of themselves into intentional, strategic holes in a story. I am essentially handing my players a pile of moral bricks and encouraging them to lay their own foundations. Giving players this opportunity fosters a relationship between the developer and the player, one where we work cooperatively to complete a story in the most emotionally satisfying way possible. As the writer I’m still in control of the major points, but I am leaving windows of opportunity to create a narrative that gives the player the ability to consider a lesson if they choose to, versus simply telling them what the lesson is.

Sometimes, a player just wants to talk to the creatures. And sometimes, as writers, we should let them.

Published: Aug 13, 2020 01:00 pm